A Roadmap For India’s Aero-engine Development & Production Ambitions

Insighteon Consulting, a Delhi based aerospace and defence consulting firm, ran an interactive wargame from August 23 to 25 2022, with the aim of ascertaining a roadmap for the development of an aero-engine ecosystem in India. Multiple analysts with varied experience working at relevant fields participated in the exercise, representing all stakeholders.

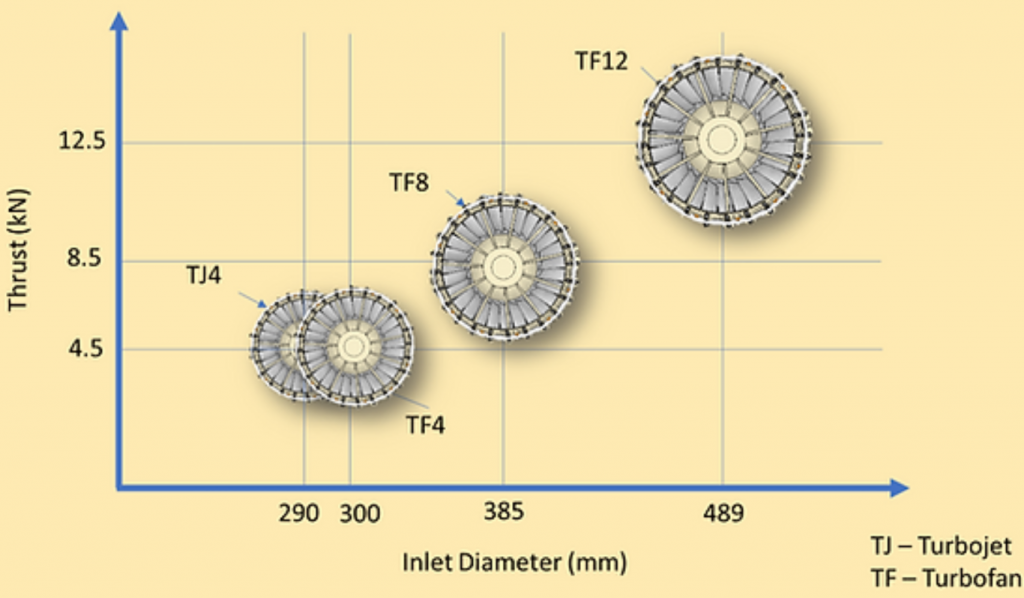

This included Paninian India, a startup which recently announced that it had designed and validated the performance of a 4.5kN turbojet engine. The firm is developing a family of turbojet and turbofan engines in the 3-12kN class.

Raghu Adla, the founder of Paninian India, told Overt Defense that the firm has been working on the project for over four years. It is looking to proceed with fabrication of the 4.5kN engine. While the firm does not intend to take part in engine development with thrust greater than 12kN, an AI enabled Digital Twin solution developed by the firm can be adapted for validation and maintenance of large engines. The firm is in touch with a couple of customers for its products, he said.

Such small engines, with increasing applications in cruise missiles and unmanned vehicles, are estimated by Insighteon to have a market of over $7.5 billion over the next 20 years in India. It was suggested that these engines be added to the next import embargo list – which encourages manufacture in India. Total indigenisation of gas turbine engines would save more than $38 billion dollars in foreign exchange over the next 20 years.

Developing indigenous aero-engines is a strategic necessity and it is imperative to ensure a level playing field for private firms and academia. Currently, aero-engine developments are a public sector monopoly. To diversify, the recommended route for development of small engines is a model with involvement of one public and two private sector companies. The Development cum Production Partner (DCPP) model followed by DRDO could be rethought by making it a consortium of DRDO, public sector, private sector, academia and the user.

Significantly, the wargame concluded that co-development models with foreign players will not result in a new design or enhanced capability. Rajiv Chib, co-founder of Insighteon, told Overt Defense that the wargame included experienced participants representing foreign OEMs. Such OEMs are unlikely to give away their technology when a big market like India is at stake. Despite multiple engine deals in the past involving technology transfer and licence manufacture, India has been unable to achieve self-sufficiency in design and manufacture of such engines.

India must continue its efforts to develop indigenous engines in mission mode. This includes the Kaveri engine, which is described as “future ready” as a dry engine without afterburner. Although the Kaveri failed to be ready for the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) Tejas, the engine is suitably placed to power a variety of UCAVs in the 3-8 ton class, including the DRDO Ghatak.

One of the main reasons for the initial failure of Kaveri was the lack of testing infrastructure, which alone caused a six year delay. This included the absence of a High Altitude Engine Test Facility and a Flying Test Bed for which India relied on Russia. These facilities should be developed urgently and made available to private firms and academia. Marginal additional investments into Kaveri would also help to achieve the planned 110 kN aero-engine target goals in a faster time frame.

For the development of the 110kN engine for the AMCA fifth generation fighter, a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) model was concluded to be the most effective. The SPV model is already planned to be used for HAL’s Indian Multi-Role Helicopter (IMRH) program and also in AMCA. This would involve DRDO, two private sector firms and the preferred foreign consultant. It was concluded that the Indian Air Force requirement for 114 multi-role fighters might provide an opportunity to leverage knowledge gaps.

The SPV could work under the overall guidance of a proposed body named National Commission for Aero Engine Development (NCAED). NCAED would have complete control over planning, design and development, production, spares, materials, certification and funding. It would reduce bureaucratic layers in decision making. It was suggested that in case of funding issues, the government could revisit its proposal of floating national defence bonds.

India largely relies on imported engines for aerospace applications. However the Kaveri, HAL’s PTAE-7 turbojet, STFE and smaller engines for UAVs are being readied for various applications. On the rotary wing front, HAL produces Safran’s Ardiden engines under licence for various helicopters while a joint venture will be created for engines for the IMRH. Development of aero-engines for defence applications would also lead to self-sufficiency in marine engines and commercial aircraft engines.

Header Image by Vayu Aerospace Review.