NATO’s Atlantic Supply Lines and the Soviet Submarine Threat

During World War II, the German Kriegsmarine and its submarines posed a major threat to the Allied war effort. Throughout 1942 and early 1943, the Germans saw increasing successes, sinking 108 merchantmen in March 1943 – most of them in convoys. The threat was eventually defeated as multiple anti-submarine systems and countermeasures were developed and deployed by the allies, leading to a major increase in German losses and a major drop in the scale and effectiveness of German convoy raiding. Nevertheless, the memory of the Battle of the Atlantic lived on, and as the Soviet Union acquired German technology after the war, some Navy reports warned that the USSR had the industrial capacity to build a fleet of up to 2,000 submarines by the 1960s. These reports were grossly exaggerated, but the Soviet Submarine force did see significant buildup during the coming decades. By the late 1980s, the Soviet fleet numbered close to 300 submarines – twice as many as there were in service with the US Navy. The possibility that this force could choke off NATO sea lines of communication (SLOCs) connecting North America and Europe in the event of a hot war, became a primary concern for American naval leaders.

However, while the Soviet submarine force was significant, its threat to NATO SLOCs in the 1980s was actually limited due to a number of factors including (1) Soviet force design, (2) Soviet strategic planning, (3) the technological and military balance, (4) geography and (5) logistics. Given these constraints, the Red Fleet would likely be unable to pose a significant challenge to NATO SLOCs. Understanding why the much more capable Soviet submarine force offered a lesser challenge to SLOCs than the Germans did can offer useful insights for thinking about challenges to SLOCs in modern Atlantic and Indo-Pacific scenarios.

Unlike the German Kriegsmarine, the Soviet submarine force was not primarily designed for commerce raiding. Rather, Soviet submarines were designed to go up against NATO military vessels, or to serve as platforms for nuclear weapons. Soviet submarines tended to carry relatively few torpedoes but had many launch tubes. This meant that they were well suited for attacking NATO forces off the Soviet coast as they could attempt to saturate fleet defenses (likely in combination with aircraft and surface vessels) and then resupply at nearby ports. However, against unarmed commercial vessels, a large amount of launch tubes is redundant. Rather, the key factor is the limited supply of torpedoes on each Soviet boat. Given the accuracy and reliability of these systems, as well as Soviet doctrine emphasizing attacking from a distance (which would likely lower accuracy further), the amount of damage to NATO shipping that the submarines could cause before being forced to return to base would be small. A submarine force tailored for commerce raiding would carry many more torpedoes on each boat.

Furthermore, Soviet plans and doctrine did not emphasize commerce raiding, meaning that it is unlikely that significant Red Fleet resources would be dedicated towards this task. First of all, Soviet war plans emphasized a quick and decisive land campaign. This campaign would be decided in a matter of days or weeks, limiting the importance of commerce raiding. Attacking SLOCs would be most impactful in a prolonged conflict where such actions could result in a culminative strategic effect. Second of all, even if the USSR wished to intercept the initial surge of reinforcements arriving from the US in a short war scenario, submarines would not be the ideal platform to achieve this. A surge of Soviet submarines would almost definitely be detected due to NATO’s sensors in the Greenland, Iceland, UK Gap (GIUK). This means that sending out a large force of submarines before the conflict starts into the Atlantic would provide strategic warning to NATO, while waiting until the beginning of the conflict to surge boats towards the Atlantic could mean they would arrive on station too late to be relevant to Soviet plans. Instead, if the Soviets wished to disrupt logistics, they could have targeted ports and prepositioned weapons stockpiles with conventional and nuclear weapons. Finally, the use of submarines to focus on commerce raiding would leave the NATO fleet unchecked. This means that in a short conflict, NATO naval airpower could operate unchallenged, NATO could launch attacks on Soviet infrastructure in the North, and NATO could even threaten to land a seaborne force in the Soviet North. Therefore, the dedication of large Soviet submarine resources towards intercepting SLOCs would not be consistent with Soviet war aims.

Moreover, the Soviet Union adopted a “Bastion” strategy which aimed primarily to use the fleet for the defense of coastal waters. Soviet submarines were often observed training in coordination with surface vessels and aircraft, implying that independent action (as would be needed to intercept SLOCs) was not a central part of Soviet doctrine. The Soviet Union was further spooked by 1980s NATO and US allied fleet exercises in the Atlantic and Pacific which practiced strikes on targets like Vladivostok. This further pushed the fleet to adopt a defensive mindset and move away from training for offensive operations, which had been more common in the 1970s.

Up to this point, this analysis has focused on Soviet force design and plans. However, NATO capabilities are also an important part of the equation. In the 1980s, NATO had a significant advantage in anti-submarine warfare (ASW) technologies. NATO possessed specialized submarines meant for hunting Soviet boats, helicopter-based ASW systems which could operate from land and from naval vessels, as well as ASW fixed-wing aircraft. These systems were reinforced by cutting-edge sensors mounted on a large variety of platforms. Before the 1980s, patrol aircraft, carrier battle groups, surface action groups, and submarines were expected to operate independently. However, in the 1980s, the US Navy’s Strategic Studies Group developed a combined arms approach to ASW warfare which would have further expanded this advantage. For example, US submarines could remain on station tracking Soviet boats for much longer and they could rely on NATO ASW aircraft to sink Soviet boats rather than being forced to expend their own torpedo stocks and return to base. With modern command and control enabled by second offset technologies, the ability of Soviet submarines (which already were designed primarily for other tasks) to threaten SLOCs beyond the Green-Iceland-UK gap would be further put into question. The Soviet submarine force would likely have suffered significant attrition.

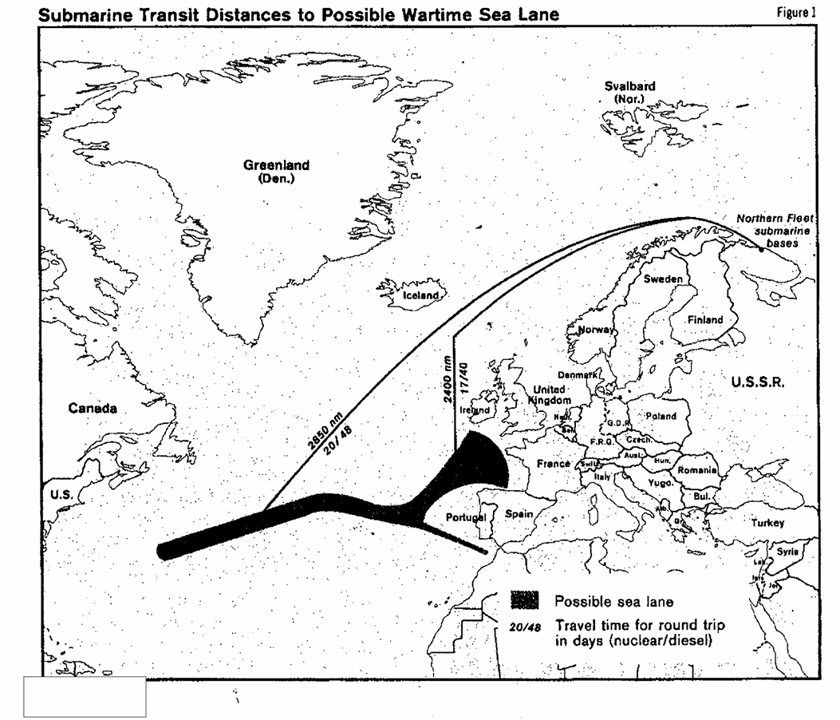

Finally, geography and sustainment must also be factored in. To intercept NATO SLOCs, Red Fleet boats would have to travel from distant bases in the Soviet far North. This means long transit times and a hard limit on the time that Soviet submarines could remain on station. Conventional boats would need 20 days to reach positions beyond Ireland, and nuclear boats 8.5 days. On average, these vessels could only remain on station for 15 days before having to return home. Back at base, the boats would have to undergo maintenance and refitting periods of about 25 days. Altogether, this means that to be on station for 15 days, a conventional boat would have to spend 65 days in transit or in the docks. Therefore, if the entire Soviet submarine fleet were committed to interdicting SLOCs, only about 19% of it could be on station at any given moment. This does not consider the reliability of Soviet boats, and the high rate of attrition they would likely suffer while trying to cross the GIUK gap (twice per patrol) and braving NATO’s ASW defenses. Moreover, even though there were 249 submarines in the Soviet fleet as of 1979, only 127 were in the Northern fleet. The rest would not be geographically positioned to pose a credible threat to NATO SLOCs in the Atlantic. Of those submarines, 87 were torpedo attack variants. Therefore, only 16 boats could actually be on station at one time if all of these were committed. This assumes sustained operations and does not factor in inevitable attrition and mechanical problems which would further reduce this number.

The model used in the CIA’s 1979 report considers most of these limitations, but shows that even under worst case scenario, the disruption to NATO SLOCs would be negligible. Assuming 20% attrition (not factoring in NATO ASW advancements), an optimistic accuracy rate for torpedoes, and a very quick supply and refit time at Soviet submarine bases, the use of the entire Northern fleet to interdict Allied shipping could cause at most 5% losses in trade volume over the span of the year. This would not be a decisive factor in a NATO-PACT conflict. While a surge approach could lead to very heavy initial losses, and the impact of a more credible risk to shipping in the early days of the conflict is beyond the scope of this analysis, it is worth noting that this worst-case scenario would have required the Red Fleet to completely abandon its primary tasks of securing Soviet territory and intercepting aircraft carriers. Moreover, there appears to be little reason to assume that the USSR could selectively intercept ships carrying more valuable military supplies. These would be largely indistinguishable from civilian cargo transports, and fast merchant ships in particular would be hard to intercept for the Soviet navy.

Based on this analysis, it is clear that the USSR lacked the advantages which enabled the Kriegsmarine to successfully intercept Allied shipping during WWII. First, Soviet doctrine and force structure was not designed for commerce raiding, while German U-boats were specifically designed for intercepting Allied merchantmen. Second, the Red Fleet would have had to defeat considerable ASW defenses. In the early stages of WWII when the U-boats seemed to have the upper hand, key Allied ASW technologies and doctrine had not yet matured. However, once these came online by mid-1943, U-boat losses skyrocketed, and their anti-shipping operations became unsustainable. Even before this period, almost all allied merchant losses to submarines occurred in the “air gap” between the UK and US. In the 1980s, there would be no such air gap. Soviet submarine losses would have proved unsustainable in a very short period. Finally, Germany had a better geographic position. The Third Reich was able to contest control of the Mediterranean (supported by air forces and Italy), and had bases in Brest which gave the Kriegsmarine prime access to the North Atlantic. The Soviet Union was not as fortunate. Its bases were far removed, limiting the number of submarines that could be on station beyond the GIUK gap, and the length of these deployments (particularly when considering limited Soviet torpedo armament). Finally, an aspect which was not considered in depth in this analysis was intelligence. German B-Dienst offered the U-boats excellent intelligence on targets; Soviet intelligence would have likely been unable to meet similar expectations. Moreover, thanks to NATO sensors, NATO would have had a major intelligence advantage.

In summary, Soviet doctrine, strategy, and force structure made it unlikely that significant submarine resources would be committed to contesting NATO SLOCs in the 1980s. Even if they were, NATO ASW and sensor capabilities, geographic realities, and the technical limitations of Soviet submarines, would make this campaign unsustainable and unlikely to cause major damage. This is true even for the most concerning scenario- a large-scale surge of Soviet submarines at the beginning of the conflict. This stands in sharp contrast to the Kriegsmarine of WWII, which was specifically designed for intercepting allied shipping, and before mid-1943, was not faced with the same limitations (like intelligence, geography, and technology) which would have constrained the Red Fleet.

Looking at Soviet submarine capabilities at the Red Fleet’s peak provides some insight for what outcomes the Russians, which inherited this fleet, could hope to achieve against NATO. Today, the Russian submarine force is a shadow of itself, fielding only 64 submarines total—and many of these are in the Pacific. Considerations related to strategy, force design, geography, logistics, military balance, intelligence, and how oceangoing trade today is different than in the past, also cannot be omitted when trying to assess the balance between China and the liberal democracies in the Indo-Pacific.