If South Korea Wants to Go Nuclear, It Should Consider Tactical Options

If South Korea wants to go nuclear to respond to its evolving threat landscape, it needs to think carefully about what type of nuclear arms it should acquire. The best solution is a tactical weapon system with limited range which can deter Pyongyang most effectively while limiting repercussions for Seoul’s relationship with its other neighbors.

Voices calling for South Korea to develop a nuclear arsenal have been growing louder. North Korea is rapidly expanding its nuclear capabilities, while refusing to rule out a nuclear first strike. China is building up its nuclear forces just as rapidly. On the other side of the world, the war in Ukraine has highlighted the importance of nuclear status. Having given up nuclear arms, Ukraine failed to deter Russia. And, amidst this revival of nuclear threats, global governance surrounding non-proliferation is in decline. Old arms limitations treaties were largely designed to balance US and Russian arsenals; they now seem outdated.

South Korea also has reason to doubt the credibility of the US nuclear umbrella. America’s arsenal of tactical nuclear weapon systems has shrunk greatly, with most systems of this class such as the TLAM-N being phased out. While the US still has some tactical air-dropped nuclear weapons, America’s increasingly limited ability to respond to tactical North Korean nuclear strikes in kind may force the US to choose between a conventional response and further escalation. Recent US actions towards Europe and Canada have also brought the political dependability of the US into question— something which is increasingly pressing now that North Korea is developing the capacity to threaten US cities. And, unlike in Europe where France and the UK maintain significant nuclear arsenals, there is no Asian alternative to the US nuclear umbrella.

The stakes for Seoul are high. If North Korea cannot be deterred, the devastation which South Korea will face will be on an apocalyptic scale, particularly if the DPRK resorts to a nuclear first strike. Any war would pose an existential threat to the Kim regime, and given South Korea’s conventional superiority on the Korean peninsula, Pyongyang can only hope to offset the ROK’s advantage through unconventional means. One likely scenario would be a nuclear strike on South Korean ports and airports to cut South Korea off from external support in the war’s opening weeks.

In order to prevent this worst case scenario, Seoul must demonstrate to Pyongyang that the DPRK cannot gain an advantage from escalating the conflict to the nuclear level. This is only achievable if the ROK has nuclear weapons at its disposal which can be used to retaliate should the DPRK choose to carry out a nuclear strike. But if it were to go nuclear, why should Seoul choose to focus on tactical nuclear capabilities in particular?

South Korea’s primary goal is to deter North Korea. Yet nuclear proliferation can threaten to alienate allies and antagonize China which could in turn weaken South Korea’s deterrence. The PRC has been sensitive to military buildup in South Korea, even when its aimed at the DPRK. One major example has been the Chinese response to the 2017 deployment of THAAD air defense batteries to South Korea. Even though the system was clearly aimed at counteracting Pyongyang’s growing missile capabilities, Beijing raised concerns that THAAD radars could be used by the US to monitor Chinese military activity. In response, China imposed significant economic consequences on Seoul.

Meanwhile, relations between Tokyo and Seoul have often been cool. Even if the threat of a South Korean nuclear strike on Japan is farfetched, a South Korean capacity to hit Japan with nuclear weapons could be a source of political tensions. For decades, the Tokyo-Seoul relationship has been a tinderbox, easily flaring up over seemingly trivial issues. Often, this is a function of domestic politics and sentiment rather than calculated strategic considerations.

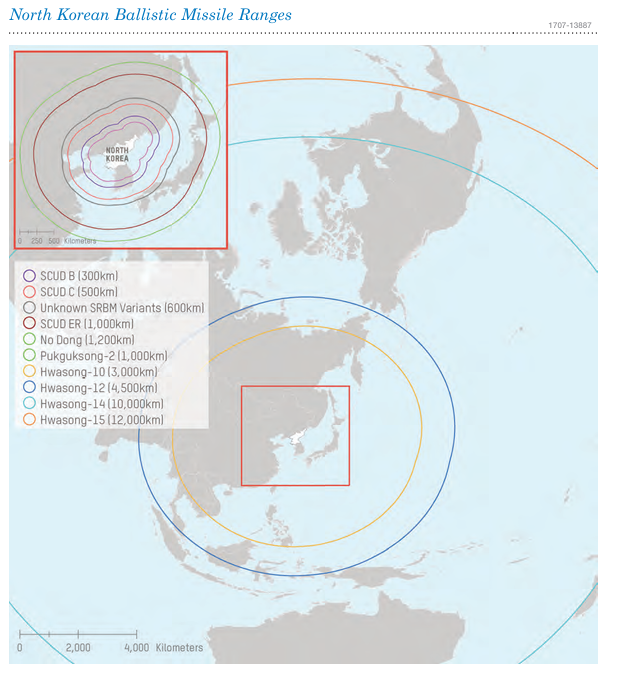

Tactical nuclear weapons could be the best option to offset these concerns. A tactical system could be designed with limited range, threatening Pyongyang and major North Korean facilities without being able to hit the capitals of Japan and China. Limiting the range of the delivery system could be particularly useful, given that the accuracy and extended range of modern missiles and aircraft makes even theoretically “tactical” weapons inherently dual-use. Gone are the days of atomic cannons with limited effectiveness beyond the battlefield. An F-35 with a “tactical” nuclear warhead can travel over 1,000 miles. And ultimately, if a weapon is tactical or strategic is primarily a function of how it is employed— is it used to achieve battlefield effects or strategic effects? Preventing this dual-use risk requires a careful, calibrated choice of delivery system. The weapons must be designed to not be compatible with longer range systems.

Second of all, tactical weapons would be a more effective deterrent against Pyongyang. Modern nuclear weapons are inflexible, particularly with the strength of the nearly century-old nuclear taboo. The Taiwan Straits crises in the 1950s showed the limitations of Eisenhower’s doctrine of massive retaliation; few targets are worth the cost of nuclear escalation. Countless conflicts since then, including Ukraine today, have underscored that lesson. With more limited nuclear capabilities, the choice for Seoul in responding to a North Korean first strike would not be between conventional strike and further escalation by using a more potent class of nuclear weapons. Instead, Seoul would be capable of threatening to retaliate in kind, making the threat of a nuclear response more tangible.

Moreover, even if North Korea were to decide that nuclear strikes are still necessary, the potential for South Korean retaliation could push Pyongyang to opt for a more limited first strike. Pyongyang retaining a latent nuclear capability following a first strike could incentivize Seoul to limit its retaliation so that it does not invite further North Korean strikes. Moreover, Seoul would not have to carry out as many nuclear strikes to get even with North Korea.

If Seoul wants to get the most out of an indigenous nuclear deterrent, that deterrent should be based around a limited, tactical capability.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of Overt Defense.