The JSDF and Article 9: From the Cold War to the Present

Japan’s pacifism has been seen by many in Japan as a core element of the postwar Japanese identity. At the center of that is Article 9 of the constitution:

“Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.”

Outlawing war was not a new concept as the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact had done so on the international-treaty-level nearly two decades before the birth of Japan’s modern constitution. However, by renouncing war as an instrument of policy and the right to maintain war potential at the constitutional level, Japan became unique among the world’s major powers due to the severity of restrictions on the use of force and the fact that they were enshrined in the constitution. While commitment to this principle had initially been high, it began to erode as early as 1950 with the establishment of the National Police Reserve (NPR).

Today, while the constitution remains unchanged, the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) maintains what under most conventional interpretations would be considered “war potential” which firmly places it among the world’s leading military forces. Moreover, government policy is in a position which can hardly be described as absolutely forfeiting the right to war.

It is important to note that Japan’s supreme and high courts have refused to deal explicitly with the constitutionality of the JSDF calling it a “political issue”. Therefore, Japan’s military policy and approach to Article 9 has always been largely based on executive branch interpretations.

Policy Before the JSDF

Despite the strong wording of Article 9 barring Japan from maintaining war potential and initial claims by the government that military forces were outlawed for all purposes, a US-trained paramilitary force called the National Police Reserve (NPR) was set up as early as 1950. In 1952, it would be renamed to the National Safety Force (NSF). The NPR was legally a police force and maintaining internal security following US military redeployment to Korea was its main goal. Nevertheless, the force was modeled after the US army and equipped with weapons like rocket launchers which clearly had little use in a non-military context. The government clearly understood the constitutional issue with this force as it went to great lengths to provide plausible deniability for any accusation that the NPR or NSF were military forces. Tanks, for example, were referred to as “special vehicles” while NPR personnel retained police ranks such as “inspector”.

While conservatives wished to amend the constitution and Article 9 ever before the Constitution was formally adopted, at this early stage it was highly popular with the majority of the public. The main driving factor for Japanese militarization was actually the United States. The US had initially hoped to see China play the leading role as an armed partner in Asia but the defeat of the nationalists in the Chinese Civil War dashed these hopes. The outbreak of war in Korea in 1950 further added to this pressure and the US government found that their own initial insistence on a pacifist Japan was now coming back to haunt them.

In the early 1950s, Japan was heavily dependent on the US for economic aid, security and diplomatic support and was not in a position to outright deny American requests for the establishment of a paramilitary force. However, due to Japan’s fragile economic situation, the political controversy of such a force, and the belief that a large military was not indispensable for upholding Japan’s security at the time, the 1948-1954 Yoshida administration resisted military expansion. When the US called for a Japanese military of 300,000, Yoshida only agreed to a much smaller force of 110,000 and refused to consider any expansion past 180,000 men. The basic policy of relying on the US for security while Japan focused on economic growth came to be known as the Yoshida doctrine.

Creation and Entrenchment of the JSDF

Japan reorganized the NSF as the JSDF in 1954 with the passing of the 1954 Self-Defense Forces Act (SDF Act) which clearly established air, land and sea branches of the armed forces despite the constitution prohibiting such action. The government simply decided to interpret war potential as anything beyond the vague notion of a minimum required for self-defense. It was also with this law that Japan’s de facto military was officially tasked with defending Japanese territory against external aggression, marking a clear departure from the previous presentation of the organization as an internal security force. This would be questionably justified in the 1970s by explaining that Japan has a right to individual self-defense but not collective self-defense under the Constitution.

What exactly the JSDF is allowed to do is prescribed in chapter six of the law which has seen 162 changes between 1954 and 2019. However, most of these are only related to technical matters of military organization rather than key policy changes.

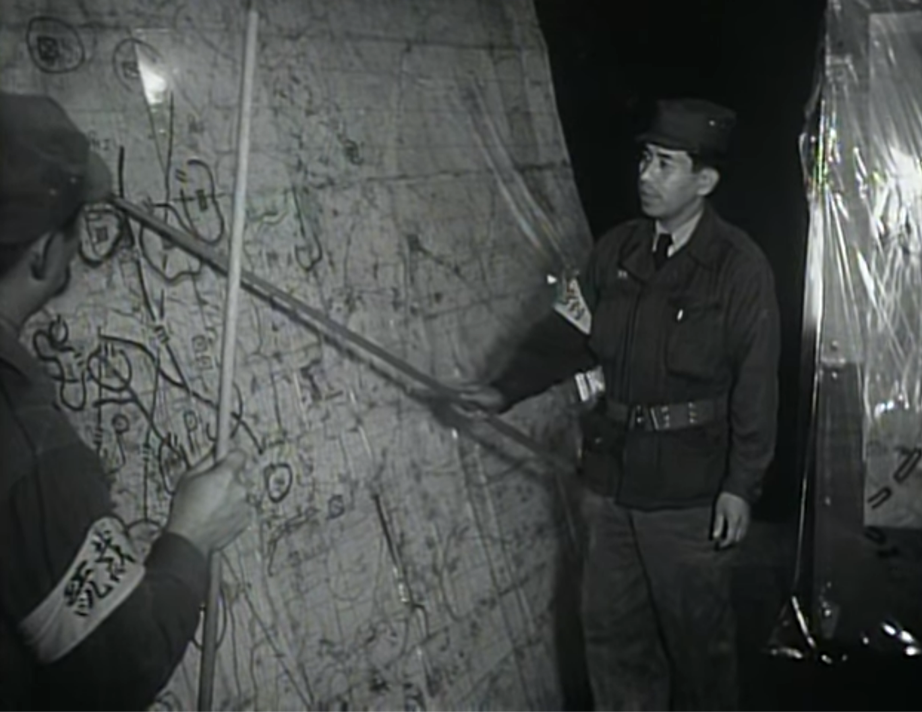

(Big Picture, Episode 319, US Army Pictorial Service, 1955)

Nevertheless, the new basic interpretation of Article 9 was not yet set in stone at this point. In 1954, Yoshida lost power and was replaced by Hatoyama. Between 1954 and 1957, the Hatoyama Administration attempted to find an alternative to the Yoshida doctrine and create an international environment in which Japan could be secure without being militarily reliant on the US. The security treaty with the US was a controversial issue and arguably meant that Japan would be complicit with a military alliance which itself could be seen as something incompatible with Article 9 pacifism. However, after Hatoyama’s attempts to reach out to China and the USSR ended in failure, the 1957-1960 Kishi administration would return to the Yoshida doctrine and succeed in revising the security treaty in 1960. After this point, the security treaty issue would lose its status as a key and controversial political issue allowing Japan’s government to maintain a consistent stance in support of the treaty as both constitutional and a cornerstone of Japanese security. While issues tied to the US presence in Okinawa would remain a controversial element of Japanese politics, after this event, the basic outline of Article 9 interpretation became entrenched for decades.

(Big Picture, Episode 319, US Army Pictorial Service, 1955)

The rest of the Cold War saw relatively little change in government policy towards the JSDF under Article 9. As security ties with the US remained strong, there was no need to significantly expand the capabilities of the JSDF or change the basic policy that the JSDF existed to provide minimum self-defense capabilities. Attempts at change could only lead to political issues for incumbents and could needlessly put additional burden on the economy. Moreover, bringing up the JSDF to a level where it could resist Soviet invasion without US support would have been unrealistic. Hence, while the Cold-War-JSDF slowly reformed and expanded as updated guidelines clarified some policy positions, the government’s basic interpretation of Article 9 remained constant. The JSDF would exist as a minimum necessary defense force which the government would not deploy abroad. War potential would remain limited by the idea of “minimum necessary” equipment for defense which, while vague, de-facto translated into policies like a military spending cap of 1% GDP and a ban on weapon exports. This was reinforced by formal adoption of the Three Non-Nuclear Principles by the Diet in 1971 which solidified the long-standing policy that nuclear arms will never be fielded by Japan or deployed to Japan. It is worth noting, however, that in nominal terms, Japan was among the leading military spenders by the end of the Cold War with the JSDF primarily configured to repel a Soviet invasion of Hokkaido.

After the Cold War

A major change to Japan’s basic policy came as a result of the shock of the Gulf War. Despite significant financial contributions and in light of Japan’s significant regional interests, Japan’s refusal (and inability) to deploy the JSDF in support of the anti-Saddam coalition was received very poorly by international partners and, particularly, the US. This came as a shock to Japan which saw its model pacifism as a strong point of its diplomatic image and led to the government reconsidering its policy regarding JSDF deployments. A plan to stretch the interpretation of the JSDF law to its absolute limits and allow for a refugee evacuation airlift collapsed due to strong opposition to troop deployment among not just the public but also within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). However, as the repercussions of Japan’s paralyzed crisis response became clearer, opinion shifted and 1991 saw minesweepers deployed to the Persian Gulf to assist in post-war minesweeping.

The deployment of the minesweepers was not incompatible with government interpretations as Article 9 as it was allowed under the 1954 SDF law. Nevertheless, the decision shifted policy debate from whether the JSDF should be allowed to deploy abroad to how the JSDF should be deployed abroad and changed a long-standing informal precedent. This began a chain of events which led to the incremental expansion of what the JSDF was allowed to do under government interpretations of Article 9.

In 1992, a new law was passed which allowed the deployment of the JSDF to UN missions in a noncombat capacity, something that before the Gulf War would have never been seriously considered. Japanese peacekeepers became an increasingly common sight globally from Cambodia to South Sudan.

With the political controversy over an expanded JSDF role being greatly reduced, Japan’s governing conservatives now found themselves in an environment where there was less and less strong universal resistance to expanding the role of the JSDF. Militarization remains unpopular among the public at large, but after the LDP regained power in 2012, the Abe administration was put in a position where substantial changes could now be made. Further concerned by China’s significant military expansion and the growing realization that the dictatorship is becoming a significant threat to Japan and the region, the Abe administration decided to lift limits on using the JSDF for collective self-defense in 2014. Abe’s decision is arguably the largest change in interpretation of Article 9 since 1954.

Under Abe and subsequent administrations, significant investment has been made into the JSDF and calls for revision have become louder. The force is also being reorganized and re-equipped away from fighting a ground war in Hokkaido towards resisting China in the seas and islands South of mainland Japan. Doctrine and equipment suggests that national self-defense remains the focus of the JSDF. For example, the limited range of Japanese submarines compared to Australian or American counterparts limits their utility far from Japanese shores. Nevertheless, the growing range and number of Chinese missiles has forced Japan to develop a strike capability which blurs offense and defense. Thus, while Article 9 remains popular with the public, the changing strategic environment and continued erosion of the article by Japan’s ruling conservatives makes it more likely than in any previous decade that the constitution will be revised to explicitly permit the JSDF and thus put issues regarding its constitutionality to rest.