Culture and Nostalgia — Russia’s Identity and War in Ukraine

The Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine, to the West, is an unjustified and illegal war. The invasion in February 2023 was a significant event for international politics. The majority of countries rallied to support Ukraine and condemn Russia.

Russia of course anticipated this response. But Russia felt threatened by NATO expansion eastward, and had to act. It took a calculated risk in starting a “special military operation” against Ukraine.

Realist doctrine would say exactly that. Russia was acting defensively against NATO and was rational about its decisions, knowing the risks and consequences of going to war with a western-aligned country.

A Liberal explanation might say that because Russia is already under many sanctions by Western countries, coupled by its authoritarian regime, it feels it is able to defy liberal rules and norms as it is already excluded from the neoliberal order.

These concepts and explanations have some truth to them, but Russia’s invasion is not purely motivated by material goals. Russia did not invade Ukraine simply because it could, or because it was threatened solely by NATO.

It is not as black and white as Western media portrays it, and it goes much deeper than a good guy/bad guy approach. This is a very nuanced affair and requires deeper observation and analysis.

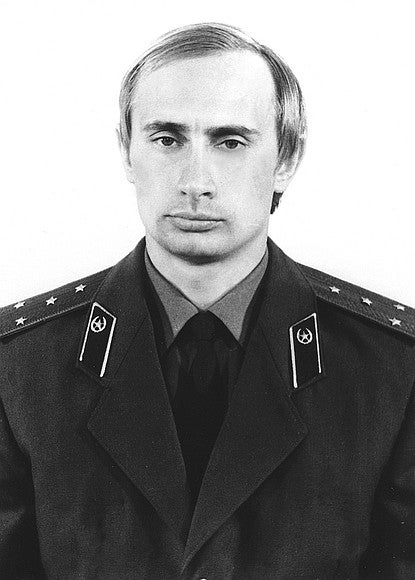

By exploring a Constructivist approach to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, taking into account social factors can reveal what the more mainstream international relations theories such as Realism and Liberalism cannot. One must take into account the culture, attitudes and memory of the Russian people, the Kremlin, and most importantly, President Vladimir Putin.

Russia’s military doctrine and strategic policy is determined by their strategic culture. In essence, the civilian government’s perceived view of how the military should act determines how the military does act.

Russia’s military doctrine has historically been an offensive one, as seen during the era of the Cold War, where the Soviet Union frequently used the Red Army to put down rebellions and unrest, such as the invasion of Hungary in 1956 after a revolution, and the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 in response to the Prague Spring.

This behaviour can also be seen in most recent times, such as the two Chechen wars in the 1990s-2000s, and the Russo-Georgian War in 2008. It is these past actions and more that define Russia’s offensive military strategic doctrine today. For Russia, it has always acted this way and is part of its identity.

This is also influenced by Russia’s government and society being extremely militarised and security-minded, because it’s how the Kremlin, and more importantly Putin, thinks it should be. According to constructivist theory, this mindset contributed to Putin’s decision to interfere in Ukrainian affairs, starting with the Donetsk and Crimea crisis in 2014.

This begs the question, why does Putin think the Russian government, society and international affairs should be so securitised and militarised? And how does this explain the war?

One could only speculate why, but one of the most obvious could be his memory and nostalgia for the former Soviet Union. Putin, an ex-KGB officer, is a notorious Soviet nostalgic who labels the fall of the Soviet Union as “the greatest political catastrophe of the [20th] century” and holds a great ambition to restore Russia to its former glory. And it is not only Putin who holds this sentiment as much of Russian society, especially the older generations, do as well.

This vigour that Putin has, fuelled by the embarrassment he shares with many Russians because of the Soviet Union’s dissolution and past political blunders, may very well influence his view of how Russia should be governed, how it should behave externally, and how its military should be used. Which is similar to how the Soviet Union governed Russia, how it behaved in the international arena, and how it utilised its military.

Putin’s opposition to NATO is one example of this, as he retains a Cold War Soviet mindset of scepticism against the West. The Soviets saw and treated NATO and the West as a threat, so he does as well. This is demonstrated by his reaction to NATO expansion eastward through his backing of separatists in the Donbas region, and annexation of Crimea, and of course, full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Putin still holds parades in Moscow for occasions like Victory Day, with troops, trucks and tanks rolling through Red Square, some donning Soviet era flags and heraldry, screens and banners displaying Lenin’s face, all to grand Soviet marching tunes which undoubtedly demonstrates Putin’s nostalgia for an ealier time.

However, this year’s Victory Parade was pitiable compared to previous years with around 8,000 personnel having participated, “the majority were auxiliary forces, paramilitary forces, and cadets” according to the U.K. Ministry of Defence, and this time only one T-34 tank. In 2020 there was an estimated total of around 25,000 personnel having participated in the parade with columns of tanks and APCs.

With the strategic failure to take Kyiv or force Ukraine’s government to the table Putin’s grab for glory may have backfired on him immensely. With Ukraine’s counter-offensive underway, only time will tell who will be the victor in this conflict, if there even will be one.

The opinions expressed in this editorial are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of Overt Defense